Introduction

This section sets out two sets of principles that collectively form the basis for these standards: Te Ara Tika principles and bioethics principles.

Te Ara Tika is a set of Māori ethical principles that draws on a foundation of tikanga (Māori protocols and practices); ‘Te Ara Tika’ means ‘to follow the right path’[1] and is used in this document as a generic set of principles commonly shared by many generations and communities of Māori; however, they have application to all people in Aotearoa New Zealand (Hudson et al. 2010).

The bioethics principles that appear here have been used in many sets of human research ethics guidelines, which have carefully established and developed their implications.

The principles presented in this chapter represent the ethical sources of the more specific ‘musts’ and ‘shoulds’ within the detailed standards in the chapters that follow.

A partnership of principles

These Standards do not ethically or conceptually prioritise either of the two sets of principles. No assumption is made that they cover the same ground in all cases. However, they do have important common ground in one sense: they involve knowledge discovery through respectful and rights-based engagement between researchers, participants and communities to advance health and wellbeing. When used together, the two sets address ethical positions of different societies, thereby strengthening ethical discourse in New Zealand.

These two sets of principles are the ethical sources of the more specific standards set out in the following chapters. For example, the guideline that participants give their informed consent to participate comes from the principle of respect for people, and from the principles of mana and manaakitanga.

The principles are guides to support ethical decision-making, and should not be used as rules. In all cases, their use requires consideration of context and a well-reasoned justification.

When the principles are described in the abstract, outside of a specific context, it may become more challenging for researchers to realise them all simultaneously; they may make incompatible demands on researchers. A well-designed research project will mitigate against obstacles and identify necessary solutions.

The principles

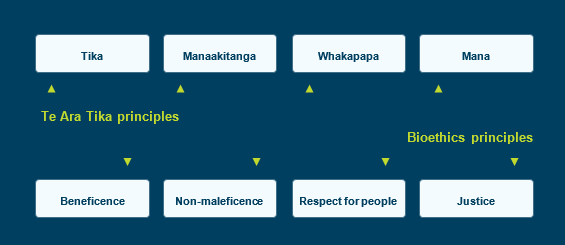

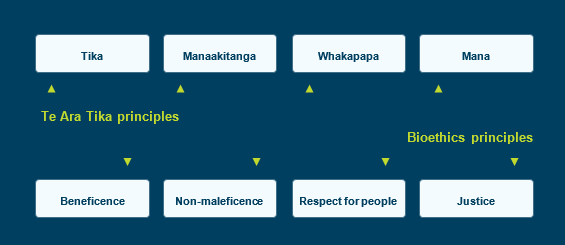

Figure 2.1 summarises the two sets of principles. The discussion that follows explains each principle in more detail.

2.1 Researchers should consider the features of a proposed study in light of these ethical principles, and should then satisfactorily resolve any ethical issues raised by the study. The application and weighting of these considerations will vary depending on the nature and circumstances of the study in question.

Figure 2.1 – Overview of Te Ara Tika and bioethics principles

Te Ara Tika principles

2.2 Te Ara Tika principles are tika, manaakitanga, whakapapa and mana.

Te Ara Tika principles

| Tika |

- Tika refers to what is right and what is good for any particular situation. Importantly, in the context of ethics it relates to the design of a study, and whether the research achieves proposed outcomes, benefits participants and communities and brings about positive change.

- Tika requires respectful relationships with Māori in all studies, regardless of the research design and methods.

- Researchers should engage with communities about which research questions are important, and reflect on the ethical issues associated with their study.

|

| Manaakitanga |

- Manaakitanga refers to caring for others, nurturing relationships and being careful in the way we treat others. Aroha (respect, love), generosity, sharing and hosting are essential parts of manaakitanga, as is upholding the mana of all parties.

- Manaakitanga relates to cultural and social responsibility and respect for people. This value requires an understanding of the appropriateness of privacy and confidentiality, to prevent harmful effects from disclosure of information, prioritise collective participation in establishing the goals and benefits of a research proposal, and empower research partnerships.

- As well as gathering data, researchers should learn to collaborate with and to give back to the community (eg, through koha and sharing ideas).

|

| Whakapapa |

- Whakapapa refers to relationships; the term encompasses the quality of those relationships, the reasons for their formation and the structures or processes that have been established to support them.

- Whakapapa in the context of ethics relates to the quality of consultation or engagement process with Māori and the monitoring of the progression of relationships through various stages of the research.

- The relationship between researchers and participants (and New Zealand communities) must involve trust, respect and integrity.

- Whakapapa reminds us that an individual is part of a whānau or wider collective. Often this can infer collective decision-making, collective information sharing, collective participation in consent processes, collective support for research data collection, collective analysis of results and participation in dissemination of results. Researchers need to assess an individual’s preferences and to involve their collective support networks.

|

| Mana |

- Mana refers to power, prestige, leadership or authority bestowed, gained or inherited individually or collectively. It infers that each individual has the right to determine their own destiny upon their own authority. Mana is an influencing factor in leadership and interpersonal and inter-group relationships, including those entailed in research. Shared knowledge upholds the mana of research participants

- Mana relates to equity and distributive justice in terms of the potential or actual risks, benefits and outcomes of research. In that context it also concerns issues of power and authority in relation to who holds rights, roles and responsibilities. Finally, the principle of mana requires that the research process upholds appropriate aspects of tikanga Māori and respects local protocols.

|

Bioethics principles

2.3 The bioethics principles are beneficence, non-maleficence, respect for people and justice.

Bioethics principles

| Beneficence |

- Beneficence for individuals and communities implies improving or benefiting people’s health or broader wellbeing. It is both the basic aim of good research and its fundamental justification. Health research should be designed, conducted and reported with the intention to improve outcomes. Beneficence also requires that projects have merit.

- The idea of what counts as a benefit may differ between individuals and communities. Researchers should take different views into account through mechanisms such as informed consent or community agreement.

|

| Non-maleficence |

- Non-maleficence requires researchers to avoid causing harm to individuals and communities, or to cause the least amount of harm possible.

- Individuals that choose to participate in research should be fully informed of potential harms, both to them individually and to any community to which they belong.

- At a community level, potential harms may place an inequitable burden on a community without providing them with a compensating benefit.

- Researchers must put appropriate measures in place to minimise the risk of harm, and effectively respond to any harm to individuals and communities.

|

| Respect for people |

- Respect for people underlies the general human rights principle of autonomy but is also significant in cases where autonomy – and, in particular, a person’s capacity to exercise informed consent – is reduced.

- Autonomy itself is a broad concept, encompassing individual autonomy but also relational autonomy and interdependence, and privacy. Autonomy also comprises the rights and interests of groups and communities.

- In many cases in the context of health research, respecting a person’s autonomy means giving due regard to a person’s judgement in making decisions – for example, about whether to participate in research. An important mechanism by which researchers can respect participants’ autonomy is by seeking their free, informed and ongoing consent.

- A person’s autonomy may be affected by their capacity to make an informed choice or give informed consent. This can change over time and can depend on the nature of the decision and any changes in the person’s condition and context. Diminished capacity may be permanent or temporary. A wide conception of autonomy is necessary, to reflect the diversity of available decision-making methods.

- Where a person is not able to make a decision for themselves, even after support has been offered, further measures are necessary to protect their interests and respect their wishes.

- In some cases, seeking informed consent would prevent or skew ethical research (e.g. where huge data sets are involved). In these cases, researchers are nonetheless expected to respect the people concerned, by treating their data with care.

|

| Justice |

- Justice requires that people are treated fairly and equitably. This includes fairly distributing or balancing the benefits and burdens of a study to populations and individual participants.

- Justice also involves reducing inequities in health outcomes for specific groups (e.g. particular socioeconomic or ethnic groups). In determining research questions and processes, researchers should consider how the research could reduce inequities in health and wellbeing. Researchers should also consider whether the research could increase inequities, and, if so, how they will mitigate this potential effect.

|